Random Ramblings from a Republican

Tuesday, March 30, 2004

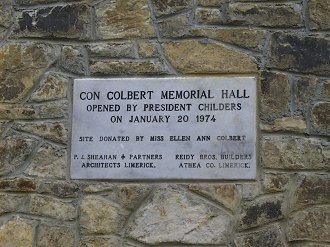

Cornelius "Con" Colbert was born in Athea in Co. Limerick in 1888. He was educated in North Richmond Street's Christian Brothers' School as was his comrade-in-arms Sean Heuston. Fresh out of schooling, he got a job at Kennedy's Bakery in Parnell Street and involved himself with Na Fianna Eireann, (National Scout Movement), an organisation so close to his heart that he spent all of his spare time cycling all over the countryside of Leinster trying to recruit people to start new sluaghs all across the province.

Con joined the Irish Volunteers shortly after their founding and was one of the organisations first drill instructors. He was quickly appointed the captain of F Company in the 4th Battalion, a position he held until the rising.

Despite his youth, he was an inspiration to his peers and his superiors, and was appointed to Volunteers Headquarters staff in 1915. In the years before 1916 he devoted his time to organising the men and boys who were to eventually participate in this historic event. His salary was paltry but he did not seem to mind and spent almost every spare penny on the furtherance of the movement.

Based on Colbert's reputation and having seen him at work, Padraig Pearse asked him to become a drill instructor at St. Enda's, where Pearse was headmaster. In spite of his growing commitments with NFE and the Volunteers, he agreed. When it was suggested that he be put on the payroll Con declined the pay and Pearse apologised and was forced to forget the idea.

In the week before the rising Colbert was sure he was going to die but he also knew it would not be in vain. He understood the concept of the "blood sacrifice" and the power of the martyr, and he was grateful for the opportunity to play his part. He was recognised as a man of high esteem to such an extreme that the British soldier who was ordered to restrain him for execution asked for the privilege of shaking his hand.

On the 8th of May 1916 Volunteer Captain Cornelius Colbert was executed by firing squad in Kilmainham Gaol for his part in the Easter Rising. Also executed with him that day were his comrades Eamonn Ceannt, Michael Mallin and Sean Heuston.

Monday, March 29, 2004

Sean Heuston was born in Dublin on 21 February 1891, the son of a clerk. Like fellow Fian Con Colbert, Heuston was educated at the Christian Brothers' School in North Richmond Street, Dublin. After his sixteenth birthday in 1907, he joined the Great Southern & Western Railway Company as a clerk. He was sent by this firm to their office in Limerick and in 1910 he joined Na Fianna Eireann, the newly founded national scout organisation. He helped to organised a branch in the city and spent all his spare time helping to teach his boys.

After serving six years with the company in Limerick, he was transferred to the Traffic Manager's Office in Dublin's Knightbridge (now Heuston) Rail Station. It was there that he would meet Con Colbert and Liam Mellows, two leading Fians. He was given charge of NFE Sluagh Robert Emmet. He was a natural leader and seemed to be inexhaustible. He was remembered by his comrades as working tirelessly at Fianna Headquarters at 12 D'Olier Street where he worked as Director of Training on details of organisation and recruit training.

As a young captain in the Volunteers during Easter Week, Sean Heuston commanded a stronghold at the Mendicity Institution. His troops were mostly Fians aged 14-17 years, inexperienced but as brave as any man. They were sent Easter Monday with the instructions to slow British advance to the GPO and the Four Courts for a few hours. A few hours turned into three days. James Connolly had given orders to Heuston to hold up the British that were heading toward the Four Courts for 3 or 4 hours to allow the garrison there as well as at Headquarters to prepare their defences. Connolly found out later that Heuston not only held his position for the few hours specified, but was still there after nearly 50 hours, until he could hold out no longer.

On Easter Wednesday morning, April 20, 1916 two Volunteer dispatchers slipped through some very dangerous areas to bring an urgent message to James Connolly from Heuston. He required immediate backup, because he and 20 young men were still holding out against several hundred British troops, who had Heuston's men just about completely surrounded. A major assault was expected at any moment and supplies and food were almost totally depleted.

Connolly was quite excited by the tenacity and bravery shown by the young Fian patriots. Commandant Padraic Pearse sent messengers back with the message that aid would be sent immediately to Heuston and his company. But almost immediately they found that it was nearly impossible to get that far unscathed and shortly after dawn on Thursday, Heuston and his remaining men had been captured.

Sean Heuston was shot on May 8 in Kilmainham Gaol Courtyard along with Con Colbert, Eamonn Ceannt, and Michael Mallin. His last message is recalled as being: "Remember me to the boys of the Fianna." He died with the dignity and courage of an Irish patriot.

*Supplementary information: Sean Heuston (Sean Mac Aodha)

Sunday, March 28, 2004

Summary of Main Events

http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/events/pdmarch/sum.htm

The People's Democracy decided to go ahead with a four-day march from Belfast to Derry, starting on 1 January. The march would be the acid test of the government's intentions. Either the government would face up to the extreme right of its own Unionist Party and protect the march from the 'harassing and hindering' immediately threatened by Major Bunting, or it would be exposed as impotent in the face of sectarian thuggery, and Westminster would be forced to intervene, re-opening the whole Irish question for the first time in 50 years. The march was modelled on the Selma-Montgomery march in Alabama in 1966, which had exposed the racist thuggery of America's deep South and forced the US government into major reforms.

Michael Farrell (1976) Northern Ireland The Orange State London: Pluto Press. (p.249)

Available police forces did not provide adequate protection to People's Democracy marchers at Burntollet Bridge and in or near Irish Street, Londonderry on 4th January 1969. There were instances of police indiscipline and violence towards persons unassociated with rioting or disorder on 4th/ 5th January in Londonderry and these provoked serious hostility to the police, particularly among the Catholic population of Londonderry, and an increasing disbelief in their impartiality towards non-Unionists (paragraphs 97-101 and 177).

Cameron Report. Disturbances in Northern Ireland. September 1969. (Cmd 532) (Summary of Conclusions; paragraph 15)

The People's Democracy March left Belfast on 1 January and arrived in Derry on 4 January 1969. The march had been organised by a group called People's Democracy which had been formed on 9 October 1968 and mainly consisted of students from the Queen's University of Belfast. The march was intended to increase the pressure for social justice and to draw attention to events in Northern Ireland since the Derry March on 5 October 1968.

Loyalists viewed the People's Democracy and the march as another attempt to undermine the Unionist government of Northern Ireland. A number of leading Loyalists, including Ronald Bunting and Ian Paisley, had indicated in advance of the march that they would be calling on 'the Loyal citizens of Ulster' to 'harrass and harry' the four-day march.

On each day of the march groups of Loyalists confronted, jostled, and physically attacked those taking part in the march. At no time did the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), who were accompanying the march, make any effort to prevent these attacks. The most serious incidents occurred on the last day between Claudy and Derry. The march was ambushed at Burntollet Bridge by approximately 200 Loyalists, including off-duty members of the 'B-Specials', and 13 marchers required hospital treatment.

The march was again attacked as it passed through the Waterside area of Derry. Later in the evening members of the RUC attacked people and property in the Bogside area of Derry sparking several days of serious rioting.

The way in which the police mishandled the People's Democracy march confirmed the opinion of many Catholics that the RUC could not be trusted to provide impartial policing in Northern Ireland. The events also further alienated many in the Catholic population from the Northern Ireland state. The march also marked the point where concerns about civil rights were beginning to give way to questions related to national identity and the constitutional position of Northern Ireland.

As what was left of the marchers continued on to Derry they were also attacked twice in Derry’s Waterside before receiving a rousing welcome in Guildhall Square.

Friday, March 26, 2004

An active participant in the rebellion in South Wicklow, Bridget 'Croppy Biddy' Dolan turned British tout and provided evidence that convicted many of her former comrades in arms. She was an perfect witness for the Brits as she knew many of the personalities in South Wicklow. She had attended many of the outdoor meetings held by them prior to the United Irishmen Rising, by which time the local unit in Shillelagh boasted 1,080 members.

Born in the County Wicklow village of Carnew around 1777, she came from a poor family and was illiterate. She was a decent horse rider and learned the skill of shodding. Those skills made her a valuable asset for the United Irish army. She was by the age of 13 "an avowed and proclaimed harlot, steeped in every crime that her age would admit of; and her precocity to vice was singular''.

In January 1798 she lost her position in the household of Captain Thomas Swan of the Carnew Yeomanry. This most likely caused some amount of hate in regards to the British presence in Ireland. It could have been at this stage that Croppy Biddy became a sworn member of the United Irishmen.

When the Rising began she said she joined the army at Tubberneering on 4 June and remained in the field with the Wicklow rebels until August, having travelled as far as northern Meath. It is believe that she spent much of her time in the mountain base camps of the Wicklow United Irishmen under General Joseph Holt. It was stated afterwards that she had an affair with Holt before his wife Hester Long joined them.

Biddy left the United Irish camp in August, when she could see that they no longer had a chance of victory, and returned to Carnew. She was not immediately suspected of insurrectionary activities, but on 16 September 1798 she was arrested by Captain William Wainright of the Shillelagh Yeomanry in Coolkenna. She agreed almost immediately to turn tout and direct the crown forces to the hideouts and weapons stashes of the United Irish rebels. She was also willing to swear anything "that she thought would please the Orange party, who supplied her with money and whiskey''. Much of her evidence to the Rathdrum court cases against United Irish suspects was certainly fabricated.

She was paid for her services until at least 1803. She continued to live in Carnew until her death in 1827 at the age of 50. She was regularly stoned and abuse was showered on her by local nationalist youths for her treachery against the Irish people.

Wednesday, March 24, 2004

I would like to re-address the issue of Republicans living in the United States being threatened with deportation by the bureaucratic nonsense spouters of the Homeland Security persuasion. What made me re-hash this issue is two-pronged. First of all is this article. A man convicted for the death of the two soldiers following the funeral of the victims of the Milltown Massacre is now threatened with deportation from the US, even though he has served his time in prison.

Secondly is the fact that Ciaran Ferry's illegal imprisonment has reached and surpassed a full year, now at 419 days. This bureaucratic injustice needs to stop. Can anyone tell me who voted for the Department of Homeland Security?

In November of 2003, after living for almost a decade as a residents of New Jersey, former member of the INLA Malachy McAllister and his family were denied an appeal against their deportation from the United States.

That same month, Ciaran Ferry's asylum appeal was denied. Ferry, a former member of the Provisional IRA, has been living and working in the US for a number of years with his wife Heaven and his young daughter Fiona. He was released from Long Kesh as a part of the Good Friday Agreement. This is an agreement that the United States Government endorses and even helped to broker, yet it refuses to recognise its provisions?

John Eddie McNicholl, a former member of the INLA was deported from the US in the summer of 2003. McNicholl, according to a statement made by the Department of Homeland Security Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement was a member of the "Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), a terrorist organization in Northern Ireland". Truth is that the INLA has NEVER appeared on the United States' list of recognised terrorist groups. This is a violation of mandates of Congress regarding their own means of identifying a "terrorist."

The hypocrisy of the current US Administration is sickening. And its stranglehold on Irish nationalists within the American Irish communities is ever-strengthening. Fears of being labeled a supporter of terrorism keep people sitting back while innocent hard-working family people are unjustly ousted from a country that was founded with ideals of justice and freedom as its building blocks.

The US/UK Extradition Treaty is just another stake in the heart of democracy and a huge threat to Irish Republicans living in America. Do not let this "Treaty" be silently enforced.

Fight the thinly veiled fascism.

Tuesday, March 23, 2004

Rory O'Connor would eventually be known as the last High King of Ireland. After Brian Boru's death in the Battle of Clontarf there remained no clear successor to the seat at Tara and the Kings of the four provinces went to war over the issue. Rory O'Connor, who had been King of Connacht since 1156, gained power and reputation gradually over time so that by 1166 he was essentially the recognised High King.

(It is important to remember that the succession to each of these kingships was often not orderly and that as king, O'Connor would not have governed even Connacht. His role was more to deal with the other kings throughout Ireland. As High King he definitely did not govern all Ireland, though there was probably some hope that he could maintain an alliance of other kings throughout the island.)

Dermot MacMurrough was the King of Leinster and wasn't at all happy that Rory O'Connor had beat him out for the High Kingship. He kidnapped O'Connor's daughter and fled Ireland to appealed to King Henry II of England (as well as countless other lands on the European Continent) for assistance against Rory.

In 1155 the Pope gave Henry II permission to "reform the Church" in Ireland. Historians are still debating if the Papal Bull of Adrian IV was genuine or a forgery used by Henry to obtain Ireland with the church's blessings. Adrian, suspected, though never proven, to be an Englishman, would have had a definite soft spot for the King of his homeland.

Dermot MacMurrough enlisted the assistance of Richard FitzGilbert de Clare, earl of Pembroke (in Wales), and a group of Cambro-Norman barons including the half-brothers Maurice FitzGerald and Robert FitzStephen, both sons of the Welsh princess Nesta. Maurice and Robert were promised the town of Wexford and the countryside surrounding that settlement, while de Clare, also known as Strongbow, was offered Dermot's daughter Aoife in marriage and promised the whole province of Leinster upon Dermot's death.

Between 1168 and 1171 the Cambro-Normans accompanied by Dermot MacMurrough and his forces not only conquered all of Leinster including Dublin, but invaded the neighbouring province of Meath and ravaged Tighernan O'Rourke's kingdom of Breifne. Dermot MacMurrough died in May 1171, and Strongbow established himself as lord of Leinster after crushing a popular revolt of the Leinster Irish.

Fearing Stongbow's new found power in southwestern Ireland, King Henry II landed with a large army near Waterford on October 17, 1171. In his Irish campaign Henry received recognition and hostages from the Ostmen (Vikings) of Wexford, as well as from many other kings in Ireland. Henry made a formal grant of Leinster to Strongbow in return for homage, fealty, and the service of 100 knights, reserving to himself the city and kingdom of Dublin and all seaports and fortresses on the east coast of Eire.

In 1175, having seen the Normans extend their control and build more cities and garrisons, O'Connor signed the Treaty of Windsor , leaving him with a kingdom consisting of areas outside Leinster, Meath, and Waterford, as long as he paid tribute to Henry II. His power continued to decline and he retired to a monastery before his death in 1198.

Henry II granted the kingdom of Meath, from the Shannon to the sea, to his own right-hand man Hugh de Lacy. By 1177 John de Courcy conquered Ulaid in northeastern Ireland. Parts of Cork went to Robert FitzStephen and Miles de Cogan, who took possession of seven small towns and exacted tribute payments from McCarthy for the remaining twenty-four hamlets. Limerick went to Philip de Braose and others, who failed to conquer any land at all on their own.

Strongbow died in June 1176 of an infection in his leg. He was buried in Holy Trinity Church in Dublin. William Marshall, his son in law, was placed in lordship of Leinster. In 1185 Theobald Walter, Philip of Worcester and William de Burgh were introduced into the northeast portion of O'Brien's kingdom of Limerick. In 1189 the kingdom of Airgialla was divided between Gilbert Pipard and Bertram de Verdon following the death of King Murchadh O'Carroll. By 1200 the roots of the Cambro-Norman influence in Ireland had been firmly planted by Henry II and his son and successor, John. What followed was a period of both Norman and Irish provincial lords and kings.

Monday, March 22, 2004

A Gaelic resurgence was in full swing, as the most significant gain for the native Irish chiefs was not necessarily territory, but liberty. In Leinster the chieftains had freedom of action as the royal government inadequately filled the gap left by the former lords of Leinster, a role later filled by the increasing power of the earls of Ormond and Kildare. In Connacht and Desmond the O'Connor and McCarthy chiefs were partially halted by the power of the Burkes and the earls of Desmond. In Thomond and Ulster this liberty was almost absolute.

There were many reasons for the decline of English royal power in Ireland in the fourteenth century. They included the impact of the Bruce invasion and the Black Death. English monarchs tended to drain the colony's resources in their campaigns against the Scots and north Welsh, and in the Hundred Years War in France. The Wars of the Roses gave kings few opportunities to recover lost ground in Ireland. To make matters worse, descendants of Norman conquerors had gone native, adopting Irish speech and customs, and abandoned their bonds with the Crown to become warlords. Only the ports and the territory around Dublin remained loyal to the Crown.

A steady deterioration of the weather across the northern hemisphere, brought a series of bad harvests in its wake. The Bruce invasion had corresponded with the Great European Famine of 1315-18, and the annals for the fourteenth century contain many references to bad seasons and cattle plagues.

The English colonists, who depended more heavily on corn than the Gaelic Irish, suffered most and, in addition, were scourged by a succession of plagues in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Black Death first appeared in Howth during the summer of 1348, and though in the following year the Annals of Connacht record "a great plague in all Ireland this year", it seems certain that the colonists in the Irish Lordship were hit hardest. The congested streets of Dublin, Drogheda, Kilkenny and other English-held towns accommodated populations of black rats, hosts of fleas carrying the dreaded bacillus. Six further outbreaks of the Black Death before the fourteenth century probably reduced the population of the English occupying colonials by 40 or 50 percent.

The government in Dublin Castle put up fortifications, dug trenches, appointed guards to hold the bridges and assigned watchmen to light warning fires when danger threatened. The area around Dublin extended from Dundalk, inland to Naas, and south to Bray. This area became known as the Pale. Apart from Carrickfergus castle, the province of Ulster was beyond the Pale.

Richard II, on the throne since 1377, was the first reigning monarch of England to visit Ireland since King John, and the only one to come to the island more than once until Queen Victoria did so. He responded to the desperate appeal of his loyal colonists, who declared that they were 'not able to find or think of other remedy except the coming of the king, our lord, in his own person'.

Landing at Waterford in October 1394 with the greatest army Ireland had yet seen, and after a hard winter campaigning, Richard brought the Leinster Irish to heel. Only too awake to the fact that the English were holding his grandsons hostage, Niall Mor O'Neill was amongst the eighty chieftains who were made to submit.

Richard sailed away in 1395, leaving Roger de Mortimer as royal governor. De Mortimer lacked the acumen necessary and foolishly made war on Niall Mor. Art MacMurrough Kavanagh declared himself King of Leinster and rebelled, with de Mortimer dying in a skirmish. Richard came to Ireland again in 1399, this time without the careful preparation of the 1394-95 campaign. It was a devastating expedition for the invading force and while he was in Ireland, at home his cousin Henry Bolingbroke rose in revolt. Richard returned to England to fight for his throne but instead lost his kingdom and his head.

Sunday, March 21, 2004

Following the initial invasion of the Cambro-Normans in the late twelfth century the installation of foreign-born lords and earls in Ireland, by King Henry II and his son John, continued throughout the thirteenth century. This gave rise to some of the great ascendacy class of Anglo-Norman families such as the Geraldines of Leinster and south Munster, the Burkes of Connacht and north Munster, and the Butlers of Tipperary and Kilkenny. These families held complete control over their designated areas.

By the beginning of the fourteenth century the expanse of the Irish feudalism was at its pinnacle. Every native leader, even the Maguires and O'Donnells in the extreme northwest, was legally the tenant of some earl or baron, or of the English king directly. However power struggles between the Irish lords and the Anglo barons, as well as rivalries among the various Irish chieftains, continued to change the landscape of political power within Ireland over the next century.

Between 1315 and 1318, the Scottish war in Britain spilled into Ireland. Edward Bruce, brother of Robert the king of Scotland, in alliance with Domhnall O Neill, king of Tir Eoghain, carried on a three year campaign against the English barons before he was defeated at the Battle of Faughart in Louth.

At the Battle of Athenry in 1316, five Irish kings were killed along with many chieftains from Connacht, Thomond and Westmeath. In conjunction with a terrible Famine from 1315-1317, the Bruce campaign devastated much of the land in the colony. In Thomond the death of Richard de Clare at the Battle of Dysert O'Dea leaves a gap which allow the O'Brien chiefs de facto independence for the rest of the Middle Ages.

At Christmas 1316, Robert Bruce joined his brother, landing at Carrickfergus with an imposing force. Early in February 1317, the brothers fought their way thru Ulster and besieged Dublin. The capital of the Irish Lordship held out successfully and the Bruces turned away to raid as far as Limerick. The winter was one of the harshest in memory, and the paucity was as severe as anyone could remember.

Edward Bruce had had himself crowned King of Ireland but the Scots were failing in their great enterprise. Robert Bruce returned to Scotland in May 1317, but Edward stayed on for another year. Then in the autumn of 1318 John de Bermingham brought an English army north from Dublin and defeated and killed Edward Bruce at the hill of Faughart near Dundalk.

For the rest of the fourteenth century the Anglo-Irish parliament in Ireland complained of decaying defenses and incompetent administration in the lands of the English lords, many of whom were living in England. The Statutes of Kilkenny were passed in 1366 as a fultile attempt to stem the increasing cooperation between the 'Gaelicized' English and the Irish chiefs.

*Part two tomorrow.

Saturday, March 20, 2004

There aren't nearly as many vampire-type myths in Irish folklore compared with those of other superstitious cultures. But there are a few prominent instances where the depraved demonic creatures appear. The most frequent is that of the Dearg-due, or Red Blood Sucker, whose most famous alleged is buried near Strongbow's Tree in Co. Waterford. She was purportedly a female of indescribable beauty who died in mysterious circumstances but rose from her grave a few times a year to wreck havoc on the men of surrounding villages. She seduced her victims by dancing until the men were stupified then she would feed on their blood. In Scotland, the vampire legend was called baobhan sith, and lurked in the mountains.

Another Irish vampire legend is Dreach-Fhoula (possibly also seen as Dreach-Shoula or Droch-Fhoula): Pronounced "droc-'ola" and means 'bad' or 'tainted blood' and while it is widely believed to refer to 'blood feuds' between persons or families, it may have a far older history.

During a lecture in 1961, the head of the Irish Folklore Commission, Sean O'Suilleabhain, spoke of a site which he called Dun Dreach-Fhoula or Castle of the Blood Visage. This was supposedly a fortress guarding a lonely pass in the Magillycuddy Reeks in Kerry, and inhabited by blood-drinking shape-shifting fairies. He did not give its exact location for the castle, and cultural historians have spent years rifling thru archives for more specific information.

It might well have been the inspiration for the name Dracula rather than Vlad Dracul. Bram Stoker, after all, never visited Eastern Europe and relied entirely on travelers' accounts.

Abhartach is only one among a few blood-drinking noble and chieftains that populate Irish folklore; and the blood-drinking undead appear briefly in Geoffrey Keating's History of Ireland, written in 1631. Stoker may well have read the legend of Abhartach in another History of Ireland, written by Patrick Weston Joyce and published in 1880. Around the same time, the original copies of Keating's work were on display in the National Museum in Dublin. Stoker probably brought together the myths of Abhartach and that of the Dun Dreach-Fhoula and somehow amagamated it with common vampire mythology.

Friday, March 19, 2004

Since I reserve the right to babble about whatever I feel like on my site, I think today I will seize upon that right to do so. I mean, hell, its in the title! I have other interests and I am going to take this opportunity to express them. Today: due to a recent need to do research in the area of demonology (religiously, historical and and in a literary context), I will be writing on a related topic.

History of Central European Vampires

The roots of vampirism are unknown, they strech back as far as Sumerian civilisation, but the strongest and most influential cultures on present day depictions of the demons are that of early medieval German and Slavic. It is from these stories that we get their deathly aversion to garlic and death by a stake to the heart.

In Slavic folklore the accounts told of depraved spirits, called ippur or a nelapsi, that would attack their former neighbors and livestock. Others of Czech origin mentioned incidents of nightmares accompanied with pain, a feeling of being suffocated, and a squeezing around the neck area upon waking up.

Another vampire-related incident was recorded by Count de Cadreras, who in the 1720s was designated by the Austrian emperor to research suspicious events in a town near the Hungarian border called Haidam. The Count investigated several cases involving people who had been dead up to 30 years who were reported to have returned from the dead to attack their relatives. When the bodies were unearthed, they showed dilatory decomposition including the flow of fresh blood when a primitive autopsy was performed. The Count ordered that the bodies be decapitated and then burned twice again. The paperwork given to the emperor documenting these procedures along with a lengthy account given by the Count to a professor at the University of Fribourg survive to this day. The town of Haidam has never been identified, nor has a place by that name ever been recorded in any other contemporary documentation.

Germany gives us the Blutsueger, or bloodsucker, and the Nachtzehrer, or time waster. These figures are best representative of the Nosferatu-esque vampirism. The Nachtzehrer were similar to the Slavic vampire in that they were known to be recently deceased people who returned from the grave to attack family members and villagers. Their undead state stemmed from an unusual death, such as a person who died by suicide or accident. They were also associated with epidemic sickness. e.g.: whenever a group of people died from the same disease, the person who died first was labeled to be the cause of the groupÂ’s death. Nachtzehrers were also believed to chew on their own extremities and cloths until they had been satiated with blood. They would then ascend from of their graves and ravage the bodies of living beings like ghouls.

In southern Germany, it was believed that those who were not baptised were drawn to immoral life and the practise of black magick. These were people who, upon death, became Blutsuegers. Also, people who commit suicide also were supposedly open to this undead state. They appeared pale and resembled a zombie from Dawn of the Dead. Bavarians safeguarded their homes by smearing garlic over their doors and windows and placing hawthorn around their houses and barns. In the folklore, Bluatsaugers could be killed by a stake though the heart and stuffing garlic in their mouths.

In Bulgaria, the people believed that spirits of the dead embarked on a journey immediately after death that visited every place they had visited during their life on earth. Their journey lasted for 40 days and then the spirit went on to its next life. However, if the dead were not properly buried, they may find that their passage to the next world was blocked, and might return to this world as a vampire. The Romanian word for vampire comes straight from the original Slavic word: opyri.

Certain people were prone to becoming vampires in Bulgarian folklore. These included people who died violently, those excommunicated from the church, drunkards, thieves, murderers, and people who practised witchcraft. Tales spread about vampires who returned to life and started their lives over in foreign towns, even so much that they would marry and have children. Their only supposed abnormality was their nightly search for blood to quench their thirst.

Methods of killing vampires include the traditional stake to the heart and a method called bottling, where a man called a djadajii would chase after the vampire with a holy icon such as a crucifix or a picture of Jesus or Mary. The djadadjii would force the vampire towards a bottle that contained its favorite food. Once the vampire was lured into the bottle, it was corked and thrown into a fire until consumed.

* These were the origins of Germanic/Slavic vampire myths and tales. More historical stuff tomorrow, I suppose.

The roots of vampirism are unknown, they strech back as far as Sumerian civilisation, but the strongest and most influential cultures on present day depictions of the demons are that of early medieval German and Slavic. It is from these stories that we get their deathly aversion to garlic and death by a stake to the heart.

In Slavic folklore the accounts told of depraved spirits, called ippur or a nelapsi, that would attack their former neighbors and livestock. Others of Czech origin mentioned incidents of nightmares accompanied with pain, a feeling of being suffocated, and a squeezing around the neck area upon waking up.

Another vampire-related incident was recorded by Count de Cadreras, who in the 1720s was designated by the Austrian emperor to research suspicious events in a town near the Hungarian border called Haidam. The Count investigated several cases involving people who had been dead up to 30 years who were reported to have returned from the dead to attack their relatives. When the bodies were unearthed, they showed dilatory decomposition including the flow of fresh blood when a primitive autopsy was performed. The Count ordered that the bodies be decapitated and then burned twice again. The paperwork given to the emperor documenting these procedures along with a lengthy account given by the Count to a professor at the University of Fribourg survive to this day. The town of Haidam has never been identified, nor has a place by that name ever been recorded in any other contemporary documentation.

Germany gives us the Blutsueger, or bloodsucker, and the Nachtzehrer, or time waster. These figures are best representative of the Nosferatu-esque vampirism. The Nachtzehrer were similar to the Slavic vampire in that they were known to be recently deceased people who returned from the grave to attack family members and villagers. Their undead state stemmed from an unusual death, such as a person who died by suicide or accident. They were also associated with epidemic sickness. e.g.: whenever a group of people died from the same disease, the person who died first was labeled to be the cause of the groupÂ’s death. Nachtzehrers were also believed to chew on their own extremities and cloths until they had been satiated with blood. They would then ascend from of their graves and ravage the bodies of living beings like ghouls.

In southern Germany, it was believed that those who were not baptised were drawn to immoral life and the practise of black magick. These were people who, upon death, became Blutsuegers. Also, people who commit suicide also were supposedly open to this undead state. They appeared pale and resembled a zombie from Dawn of the Dead. Bavarians safeguarded their homes by smearing garlic over their doors and windows and placing hawthorn around their houses and barns. In the folklore, Bluatsaugers could be killed by a stake though the heart and stuffing garlic in their mouths.

In Bulgaria, the people believed that spirits of the dead embarked on a journey immediately after death that visited every place they had visited during their life on earth. Their journey lasted for 40 days and then the spirit went on to its next life. However, if the dead were not properly buried, they may find that their passage to the next world was blocked, and might return to this world as a vampire. The Romanian word for vampire comes straight from the original Slavic word: opyri.

Certain people were prone to becoming vampires in Bulgarian folklore. These included people who died violently, those excommunicated from the church, drunkards, thieves, murderers, and people who practised witchcraft. Tales spread about vampires who returned to life and started their lives over in foreign towns, even so much that they would marry and have children. Their only supposed abnormality was their nightly search for blood to quench their thirst.

Methods of killing vampires include the traditional stake to the heart and a method called bottling, where a man called a djadajii would chase after the vampire with a holy icon such as a crucifix or a picture of Jesus or Mary. The djadadjii would force the vampire towards a bottle that contained its favorite food. Once the vampire was lured into the bottle, it was corked and thrown into a fire until consumed.

* These were the origins of Germanic/Slavic vampire myths and tales. More historical stuff tomorrow, I suppose.

Wednesday, March 17, 2004

*this is an excerpt from a book I'm currently reading called Republicanism in Modern Ireland.

A Potential Fifth Column?

The IRA as a German Proxy, 1935-39

by Eunan O'Halpin

It might be thought that the IRA's insurrectionary potential would have loomed reasonably large in the minds of British military and security officials studying problems of home defence which might arise in the case of a war with Germany. Until the spring of 1938, such a war would have been assumed to include operations based on the Irish ports and unspecified other facilities guaranteed to Britain under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. In those circumstances, even the least imaginative staff officers would surely have factored the likelihood of IRA action against British targets. Even after the April 1938 Anglo-Irish agreement ended British defence rights in independent Ireland, there was an obvious danger that the republican movement would take the opportunity to make trouble in Northern Ireland and in Britain, whether through sabotage or espionage. Yet it appears that, until very late in the decade, Britain had no inkling of the IRA's sporadic contacts with Nazi Germany which were initiated in 1935. It may be that the idea of a serious renewal of the First World War Irish separatist-German link which had produced the 1916 rising was discounted in the changed circumstances of an independent Ireland, despite how difficult and unpredictable a dominion Mr de Valera's was proving to be.

The evidence on pre-war British appreciations of the IRA's intentions, capabilities and alliances is very confused. As early as 1927, SIS reported indications that the organisation had, through international communist circles established contact in 1922 with 'the German espionage service'. This seems unlikely: the IRA had in fact reached agreement with the Soviets in 1925 to gather military intelligence in the UK, an episode of which the British seem never to have become aware. In 1927 republicans also formally resolved to take the Russian side in any future Anglo-Soviet war. In 1933 a Russian emigre reported that the IRA had concluded a pact with the Comintern (the Soviet controlled Communist International) under which large quanities of arms were to be delivered to Ireland, a report which SIS was inclined to discount because of its general suspicion of "White Russian information" as "the sources were so uncontrolled, so liable to produce tendentious matter and to be vitiated at their source" by Soviet penetration. These scraps suggest that after 1933 SIS and Mi5 may had regarded the Soviet Union, rather than Nazi Germany, as the IRA's most likely future ally. Yet in December of 1935, a decoded Italian diplomatic telegram from Dublin to Rome indicated that the Italian minister had persuaded the IRA leaders to organise propaganda in the United States in support of his country's attack on Abyssinia. It is not known how British agencies interpreted this second hand evidence of Irish republicanism' ideological elasticity. Even when the first traces of German intelligence interest in Ireland were noted in Whitehall, they do not appear to have been construed in terms of a possible IRA-German alliance: a Joint Intelligence Committee document of June 1937 on "German activities in the Irish Free State" analysed evidence in terms of the possibility of Germany seeking a military understanding with the Irish government not with the IRA which then appeared a predominantly left-wing movement.

There is no evidence to indicate that up to 1939 any British (or Irish) defence or security agency actively contemplated the possibility that Germany was forging links with the republican movement for development during a future war against Britain. It seems that it was not until the IRA launched the "S-plan" that the possibility of German manipulation was seriously considered. An early War Office advocated of irregular warfare dismissed the "completely futile and puerile attempts at sabotage being carried out by the IRA in England", and did not argue the possibility that the activity was German inspired or assisted. Despite its apprehensions about German designs, and its unfolding knowledge of German intelligence activities concerning Ireland, Mi5 concluded that there was "no evidence that German agents had been responsible for the IRA bombing campaign, though there were grounds for thinking that the Germans in Dublin...had made approached to the IRA leaders as to the possibility of cooperation in the event of war between Nazi Germany and England. They were inclined to regard the danger of Germany organising sabotage with the assistance of IRA terrorists as a very serious one."

A Potential Fifth Column?

The IRA as a German Proxy, 1935-39

by Eunan O'Halpin

It might be thought that the IRA's insurrectionary potential would have loomed reasonably large in the minds of British military and security officials studying problems of home defence which might arise in the case of a war with Germany. Until the spring of 1938, such a war would have been assumed to include operations based on the Irish ports and unspecified other facilities guaranteed to Britain under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. In those circumstances, even the least imaginative staff officers would surely have factored the likelihood of IRA action against British targets. Even after the April 1938 Anglo-Irish agreement ended British defence rights in independent Ireland, there was an obvious danger that the republican movement would take the opportunity to make trouble in Northern Ireland and in Britain, whether through sabotage or espionage. Yet it appears that, until very late in the decade, Britain had no inkling of the IRA's sporadic contacts with Nazi Germany which were initiated in 1935. It may be that the idea of a serious renewal of the First World War Irish separatist-German link which had produced the 1916 rising was discounted in the changed circumstances of an independent Ireland, despite how difficult and unpredictable a dominion Mr de Valera's was proving to be.

The evidence on pre-war British appreciations of the IRA's intentions, capabilities and alliances is very confused. As early as 1927, SIS reported indications that the organisation had, through international communist circles established contact in 1922 with 'the German espionage service'. This seems unlikely: the IRA had in fact reached agreement with the Soviets in 1925 to gather military intelligence in the UK, an episode of which the British seem never to have become aware. In 1927 republicans also formally resolved to take the Russian side in any future Anglo-Soviet war. In 1933 a Russian emigre reported that the IRA had concluded a pact with the Comintern (the Soviet controlled Communist International) under which large quanities of arms were to be delivered to Ireland, a report which SIS was inclined to discount because of its general suspicion of "White Russian information" as "the sources were so uncontrolled, so liable to produce tendentious matter and to be vitiated at their source" by Soviet penetration. These scraps suggest that after 1933 SIS and Mi5 may had regarded the Soviet Union, rather than Nazi Germany, as the IRA's most likely future ally. Yet in December of 1935, a decoded Italian diplomatic telegram from Dublin to Rome indicated that the Italian minister had persuaded the IRA leaders to organise propaganda in the United States in support of his country's attack on Abyssinia. It is not known how British agencies interpreted this second hand evidence of Irish republicanism' ideological elasticity. Even when the first traces of German intelligence interest in Ireland were noted in Whitehall, they do not appear to have been construed in terms of a possible IRA-German alliance: a Joint Intelligence Committee document of June 1937 on "German activities in the Irish Free State" analysed evidence in terms of the possibility of Germany seeking a military understanding with the Irish government not with the IRA which then appeared a predominantly left-wing movement.

There is no evidence to indicate that up to 1939 any British (or Irish) defence or security agency actively contemplated the possibility that Germany was forging links with the republican movement for development during a future war against Britain. It seems that it was not until the IRA launched the "S-plan" that the possibility of German manipulation was seriously considered. An early War Office advocated of irregular warfare dismissed the "completely futile and puerile attempts at sabotage being carried out by the IRA in England", and did not argue the possibility that the activity was German inspired or assisted. Despite its apprehensions about German designs, and its unfolding knowledge of German intelligence activities concerning Ireland, Mi5 concluded that there was "no evidence that German agents had been responsible for the IRA bombing campaign, though there were grounds for thinking that the Germans in Dublin...had made approached to the IRA leaders as to the possibility of cooperation in the event of war between Nazi Germany and England. They were inclined to regard the danger of Germany organising sabotage with the assistance of IRA terrorists as a very serious one."

Tuesday, March 16, 2004

Something new:

The Passion

I figure, since its all the rage these days, I will post a few of my thoughts on the film that has everyone talking. Don't expect them to have any amount of cohesion or be of any real intellectual value.

Gibson's Work

Amidst cries of anti-Semitism, I believe Gibson provided a fair view of last brutal hours in the life of Yeshua Ha-Nostri, son of God. He drew from different parts of the four Gospels and came out with a relative balance.

The story involves a Jew who tried to replace the established Temple of Yershalaim and center a reformed religion around him as the Messiah, the centerpiece. This was understandably greeted with horror and malice from the Temple's hierarchy. The fallacy that the Jews "were Christ-killers" involves a purposeful misinterpretation of the Scripture and Yeshua's teaching: Yeshua was made a man and came to Earth in order to suffer and die for our sins. No ethnicity, no single person, no priest, no procurator, no executioner killed Yeshua; he died by his Father's will to fulfill prophecy, and with our sins we all aided in killing him. Some Christian churches have historically been guilty placing Jews at fault for the death of Yeshua, but in teaching that, they violated their own beliefs.

I am not a terribly religious person, but I respect religion for its basal function: faith. Everyone needs something to have faith in. I am of a Catholic background and have countless credit hours in religious studies; I thought the film did better justice than any other Scripture-based Hollywood production I have seen. The overly-pious and sometimes overly full of crap Hollywood biblical epics of the 1950s and 1960s (e.g. the Ten Commandments, The Gospel According to St. Matthew) were too superficial and the religious films of the 1970's (e.g. Jesus of Nazareth, Last Temptation of Christ) were too much of a stretch in most instances.

I do have a few complaints: without a measure of knowledge of Christian scripture, one is completely lost with the film. For someone that has had very little contact with religion of any kind, the end of the film leaves them full of questions. The ride home will be spent condensing the general story of the Gospels into a 15 minute summary. But perhaps this was Gibson's initial intent; to make people talk and to think.

Another complaint is the Hollywood-y type things present in the film; e.g.: the repeated presence of Satan and the laughable portrayal of Hell; demons disguised as children attacking Judas and a tear from God that sparks an earthquake. Perhaps I'm being a bit picky, but I think it would have been just as good without those things. I understand that Satan was following Yeshua around "like a lion" (thanks Vicki), my complaint is the WAY he is portrayed; the cheesy Hollywood-esque manner in which he is shown.

The movie is brutally violent and though I've seen countless war films, I believe Gibson's film ranks ichiban on my list of blood and gore. For some, entering the theatre with thoughts of piety and a set image of this event in their heads, the movie will leave them disturbed and perhaps even speechless for a while.

Mob mentality is played up as the Sanhedrin call for Yeshua's crucifixion in the court-yard of the Roman procurator. This is a common theme in poor societies across the world and across time itself; Greece, Rome, Medieval Europe, Revolutionary France, and New York City of the mid-19th century. To control the mob is to control the power of the people. This is in no way a sign of anti-semitism. And it is only reactionary to cry "hatemonger".

Over all, as an acquaintance of mine said in reference to this movie: this is one of the best films that I never want to see again. That is a good summary of my feelings. I will not go out of my way to see this movie again; one time is enough to leave the mark Gibson desired.

I figure, since its all the rage these days, I will post a few of my thoughts on the film that has everyone talking. Don't expect them to have any amount of cohesion or be of any real intellectual value.

Amidst cries of anti-Semitism, I believe Gibson provided a fair view of last brutal hours in the life of Yeshua Ha-Nostri, son of God. He drew from different parts of the four Gospels and came out with a relative balance.

The story involves a Jew who tried to replace the established Temple of Yershalaim and center a reformed religion around him as the Messiah, the centerpiece. This was understandably greeted with horror and malice from the Temple's hierarchy. The fallacy that the Jews "were Christ-killers" involves a purposeful misinterpretation of the Scripture and Yeshua's teaching: Yeshua was made a man and came to Earth in order to suffer and die for our sins. No ethnicity, no single person, no priest, no procurator, no executioner killed Yeshua; he died by his Father's will to fulfill prophecy, and with our sins we all aided in killing him. Some Christian churches have historically been guilty placing Jews at fault for the death of Yeshua, but in teaching that, they violated their own beliefs.

I am not a terribly religious person, but I respect religion for its basal function: faith. Everyone needs something to have faith in. I am of a Catholic background and have countless credit hours in religious studies; I thought the film did better justice than any other Scripture-based Hollywood production I have seen. The overly-pious and sometimes overly full of crap Hollywood biblical epics of the 1950s and 1960s (e.g. the Ten Commandments, The Gospel According to St. Matthew) were too superficial and the religious films of the 1970's (e.g. Jesus of Nazareth, Last Temptation of Christ) were too much of a stretch in most instances.

I do have a few complaints: without a measure of knowledge of Christian scripture, one is completely lost with the film. For someone that has had very little contact with religion of any kind, the end of the film leaves them full of questions. The ride home will be spent condensing the general story of the Gospels into a 15 minute summary. But perhaps this was Gibson's initial intent; to make people talk and to think.

Another complaint is the Hollywood-y type things present in the film; e.g.: the repeated presence of Satan and the laughable portrayal of Hell; demons disguised as children attacking Judas and a tear from God that sparks an earthquake. Perhaps I'm being a bit picky, but I think it would have been just as good without those things. I understand that Satan was following Yeshua around "like a lion" (thanks Vicki), my complaint is the WAY he is portrayed; the cheesy Hollywood-esque manner in which he is shown.

The movie is brutally violent and though I've seen countless war films, I believe Gibson's film ranks ichiban on my list of blood and gore. For some, entering the theatre with thoughts of piety and a set image of this event in their heads, the movie will leave them disturbed and perhaps even speechless for a while.

Mob mentality is played up as the Sanhedrin call for Yeshua's crucifixion in the court-yard of the Roman procurator. This is a common theme in poor societies across the world and across time itself; Greece, Rome, Medieval Europe, Revolutionary France, and New York City of the mid-19th century. To control the mob is to control the power of the people. This is in no way a sign of anti-semitism. And it is only reactionary to cry "hatemonger".

Over all, as an acquaintance of mine said in reference to this movie: this is one of the best films that I never want to see again. That is a good summary of my feelings. I will not go out of my way to see this movie again; one time is enough to leave the mark Gibson desired.

Monday, March 15, 2004

My computer is currently out of order. I apologise. Hope everyone is well.

During these days it is important to remember Bobby Sands. Here are some links to sources and other sites about him.

Collection of Bobby Sands Net Resources

Bobby Sands Trust

The Diary of Bobby Sands

Bobby Sands Bio via Ireland's Own

During these days it is important to remember Bobby Sands. Here are some links to sources and other sites about him.

Collection of Bobby Sands Net Resources

Bobby Sands Trust

The Diary of Bobby Sands

Bobby Sands Bio via Ireland's Own

Thursday, March 11, 2004

Part 3:

The following is one response regarding the Hunger strike of 1980 from a man who participated: Tommy McKearney, now editor of Fourthwrite magazine. It is taken from a volume of Republican literature, Republican Voices. Information on purchasing this book can be found here. I strongly recommend buying this book, as it is a vital piece in understanding current "dissidents" who were loyal members of the Provisional Movement.

Tommy McKearney:

At that stage I was measuring my deterioration against that of Sean McKenna and I was under the impression, as distinct from what I know now, that my decline would be along a similar graph as other people. In fact this wasn't the case because my rate of decline was accelerating quite rapidly; it was telescoping. I deteriorated in two or three days and fell to the level of Sean's illness after forty days. I was unaware of my rate of deterioration and just how critically ill I was, to the extent that my parents were awarded a visit per day (before they were allowed a visit per week). I believe that the prison authorities had turned liberal and awarded us all a visit when in fact it was only Sean McKenna and myself who had this. But in deference to the sensitivity of my position the other five didn't tell me this of how dangerously ill I was.

The last few days of the Hunger Strike were tortuous, as far as I remember them. What eventually happened was that lack of food affected my kidney and they went into failure and I was no longer able to drink water, which had the effect of flushing my system. Poisons built up and damaged my internal organs. My circulations began to be disabled and I felt the sensation of pins and needles in my toes and finger tips. I also noticed blotches creeping from my toes to my knees and from my fingers to my elbows. I was also suffering from acute heartburn and burning sensations because I was unable to flush the poisons from my body. I began to vomit a bottle of green fluid every couple of minutes. It would give me a few minutes relief and then it would build up again and I would begin to vomit again. I began periods of intermittent consciousness and rationality, drifting in and out of consciousness.

On occasions I was lucid and quite conscious, and aware of what was happening; on other occasions I would have hallucinations, become unconscious or drift off to sleep, but at this stage I didn't know when I was unconscious or when I was just sleeping. The hallucinations were not like those on TV or the more garish films; they were of a strange nature. At one stage I thought someone was playing on-going ceili music in the distance and I said to myself 'the screws are doing this to torment me', but it wasn't so, there was no music and it was something in my mind.

Yet on other occasion I was surprisingly conscious, for example,. I was talking to my mother about a business premises in the village and wondering if my father could get enough money to buy it, which was a strange concern two days before the end of a Hunger Strike! At this time the prison doctors believed I had between three and five days to live. So I could go from chilling reality to the bizarre. Looking back on it now as a whole, I simply wasn't rational.

Buy the book to read the whole text.

The following is one response regarding the Hunger strike of 1980 from a man who participated: Tommy McKearney, now editor of Fourthwrite magazine. It is taken from a volume of Republican literature, Republican Voices. Information on purchasing this book can be found here. I strongly recommend buying this book, as it is a vital piece in understanding current "dissidents" who were loyal members of the Provisional Movement.

Tommy McKearney:

At that stage I was measuring my deterioration against that of Sean McKenna and I was under the impression, as distinct from what I know now, that my decline would be along a similar graph as other people. In fact this wasn't the case because my rate of decline was accelerating quite rapidly; it was telescoping. I deteriorated in two or three days and fell to the level of Sean's illness after forty days. I was unaware of my rate of deterioration and just how critically ill I was, to the extent that my parents were awarded a visit per day (before they were allowed a visit per week). I believe that the prison authorities had turned liberal and awarded us all a visit when in fact it was only Sean McKenna and myself who had this. But in deference to the sensitivity of my position the other five didn't tell me this of how dangerously ill I was.

The last few days of the Hunger Strike were tortuous, as far as I remember them. What eventually happened was that lack of food affected my kidney and they went into failure and I was no longer able to drink water, which had the effect of flushing my system. Poisons built up and damaged my internal organs. My circulations began to be disabled and I felt the sensation of pins and needles in my toes and finger tips. I also noticed blotches creeping from my toes to my knees and from my fingers to my elbows. I was also suffering from acute heartburn and burning sensations because I was unable to flush the poisons from my body. I began to vomit a bottle of green fluid every couple of minutes. It would give me a few minutes relief and then it would build up again and I would begin to vomit again. I began periods of intermittent consciousness and rationality, drifting in and out of consciousness.

On occasions I was lucid and quite conscious, and aware of what was happening; on other occasions I would have hallucinations, become unconscious or drift off to sleep, but at this stage I didn't know when I was unconscious or when I was just sleeping. The hallucinations were not like those on TV or the more garish films; they were of a strange nature. At one stage I thought someone was playing on-going ceili music in the distance and I said to myself 'the screws are doing this to torment me', but it wasn't so, there was no music and it was something in my mind.

Yet on other occasion I was surprisingly conscious, for example,. I was talking to my mother about a business premises in the village and wondering if my father could get enough money to buy it, which was a strange concern two days before the end of a Hunger Strike! At this time the prison doctors believed I had between three and five days to live. So I could go from chilling reality to the bizarre. Looking back on it now as a whole, I simply wasn't rational.

Buy the book to read the whole text.

Wednesday, March 10, 2004

Part 2:

The following is one response regarding the Hunger strike of 1980 from a man who participated: Tommy McKearney, now editor of Fourthwrite magazine. It is taken from a volume of Republican literature, Republican Voices. Information on purchasing this book can be found here. I strongly recommend buying this book, as it is a vital piece in understanding current "dissidents" who were loyal members of the Provisional Movement.

Tommy McKearney:

Brendan Hughes told us to co=operate with the medical authorities. They were monitoring our heart beat, urine samples, blood samples and weight on a daily basis, so they could tell if we were consuming protein. They could also determine the rate of deterioration of the body. For example, you can detect components of the body, muscle, bone, fat and parts of the internal organs in the blood stream. We all knew that it was vitally important to drink as much water as possible and for forty days I could drink several litres a day. I didn't notice any great loss of strength. Certainly I couldn't run and was tired but I was reasonably competent for the first forty odd days.

But I did find Sean McKenna's deterioration alarming because he had begun to deteriorate very early on, perhaps as early as the twelfth of thirteenth day. Sean was unable to leave the cell and if he did get up out of bed he was very week, very weak on his feet and he had difficulty walking without the assistance of medical staff. It surprised me that Sean had deteriorated so rapidly, but some of the prison medical people were telling us that no two bodies are identical and that there is no uniform reaction. Some people can live longer than others without food. Some people deteriorate more rapidly depending on one's state of health and previous medical history.

We were taken from H3 to the prison hospital and put in single cells in the prison ward. I began to notice a rapid deterioration in my health about this time. I went to give a urine sample and took a black out when I put pressure on my bladder I was held up by two prison medical officers and fell into their arms. Within minutes I came back to consciousness and by then I was in a wheelchair, being wheeled back to the cell by the Prison Medical Officers.

I have this to say about them [the PMOs], they treated me quite humanely during the Hunger Strike, politics apart. I won't tell any lies about them. The PMOs reassured me that I was safe in their hands. But I couldn't see anything- the world was black and my eyesight had failed completely. Within about an hour and a half my eyesight started to return, but not perfectly. I could see, but I had lost my 'horizontal hold' and everything was starting to go up and down. The next day I began to lose my left eye which was deteriorating at a faster rate than my right eye, and so to watch, or to see, or to look I had to close my left eye and use my right.

*Tomorrow, more of this bit of the interview. Buy the book to read the whole text.

The following is one response regarding the Hunger strike of 1980 from a man who participated: Tommy McKearney, now editor of Fourthwrite magazine. It is taken from a volume of Republican literature, Republican Voices. Information on purchasing this book can be found here. I strongly recommend buying this book, as it is a vital piece in understanding current "dissidents" who were loyal members of the Provisional Movement.

Tommy McKearney:

Brendan Hughes told us to co=operate with the medical authorities. They were monitoring our heart beat, urine samples, blood samples and weight on a daily basis, so they could tell if we were consuming protein. They could also determine the rate of deterioration of the body. For example, you can detect components of the body, muscle, bone, fat and parts of the internal organs in the blood stream. We all knew that it was vitally important to drink as much water as possible and for forty days I could drink several litres a day. I didn't notice any great loss of strength. Certainly I couldn't run and was tired but I was reasonably competent for the first forty odd days.

But I did find Sean McKenna's deterioration alarming because he had begun to deteriorate very early on, perhaps as early as the twelfth of thirteenth day. Sean was unable to leave the cell and if he did get up out of bed he was very week, very weak on his feet and he had difficulty walking without the assistance of medical staff. It surprised me that Sean had deteriorated so rapidly, but some of the prison medical people were telling us that no two bodies are identical and that there is no uniform reaction. Some people can live longer than others without food. Some people deteriorate more rapidly depending on one's state of health and previous medical history.

We were taken from H3 to the prison hospital and put in single cells in the prison ward. I began to notice a rapid deterioration in my health about this time. I went to give a urine sample and took a black out when I put pressure on my bladder I was held up by two prison medical officers and fell into their arms. Within minutes I came back to consciousness and by then I was in a wheelchair, being wheeled back to the cell by the Prison Medical Officers.

I have this to say about them [the PMOs], they treated me quite humanely during the Hunger Strike, politics apart. I won't tell any lies about them. The PMOs reassured me that I was safe in their hands. But I couldn't see anything- the world was black and my eyesight had failed completely. Within about an hour and a half my eyesight started to return, but not perfectly. I could see, but I had lost my 'horizontal hold' and everything was starting to go up and down. The next day I began to lose my left eye which was deteriorating at a faster rate than my right eye, and so to watch, or to see, or to look I had to close my left eye and use my right.

*Tomorrow, more of this bit of the interview. Buy the book to read the whole text.

Tuesday, March 09, 2004

The following is one response regarding the Hunger strike of 1980 from a man who participated: Tommy McKearney, now editor of Fourthwrite magazine. It is taken from a volume of Republican literature, Republican Voices. Information on purchasing this book can be found here. I strongly recommend buying this book, as it is a vital piece in understanding current "dissidents" who were loyal members of the Provisional Movement.

Tommy McKearney:

I had seen on Hunger Strike previously in Portlaoise in 1975 and it had lasted over 30 days so I wasn't totally unaware of what might happen. The first morning of the Hunger Strike I was in the H-Block with my old cell-mate Dennis Cummings. I do remember the screws coming with our breakfast and I refused it. Unlike other occasions when I had refused food and they had responded sarcastically, if not menacingly, the screws were very interested to record the fact because they were aware of what was happening. They officially confirmed that I was refusing to eat food, and the screws asked me three times.

I'd heard different stories in the past about Hunger Strikes, such as the pangs of hunger go within a few days, different things like that It wasn't my experience since for certainly 35-40 days I could still feel hunger and I was tempted to eat food. When I lost my appetite for food it was much later and it was the result of the effects of sickness and the effects of lack of food rather than and diminution of appetite.

There certainly was no noticeable physiological effects for the first twenty days. I felt a wee bit tired but I could sleep, read and write. To an extent this was tempered by the fact that we were thinking frantically about political developments and thinking about strategy. We were working as best as we could from within the confines of the prison to see if we could advance and develop the protest. We were listening form information; it wasn't a question of just being in a total vacuum, total isolation, just sitting staring. We were constantly receiving bits of information and we were constantly trying to send out wee suggestions. I suppose this activity would tend to use up some of our thoughts rather than sitting and dwelling on the lack of food.

After ten days in our original cell we were moved together from our blanket cells to a clean wing in H3; that was the first time that we were together. Brendan Hughes was OC of the Hunger Strike and he had handed the overall OC position in the jail over to Bobby Sands, at the beginning of the Hunger Strike. Brendan ordered us to stop the dirty protest when we began the Hunger Strike. We washed, had beds and wore prison pyjamas; there was no other clothing apart from the pyjamas.

In this period the screws routinely came four times a day and left our food in. The breakfast would be left with us until lunch, and lunch would be left until tea, the tea would be left until supper and the supper would be left until breakfast, and so on. The screws would record that nothing had been touched or eaten. I have since learnt that the prison authorities would measure the food with almost scientific accuracy to see if we had eaten or even touched the food. We were told by the prison authorities that there was no breach of the Hunger Strike recorded - it was certainly true in my case.

*Tomorrow, more of this bit of the interview. Buy the book to read the whole text.

Tommy McKearney:

I had seen on Hunger Strike previously in Portlaoise in 1975 and it had lasted over 30 days so I wasn't totally unaware of what might happen. The first morning of the Hunger Strike I was in the H-Block with my old cell-mate Dennis Cummings. I do remember the screws coming with our breakfast and I refused it. Unlike other occasions when I had refused food and they had responded sarcastically, if not menacingly, the screws were very interested to record the fact because they were aware of what was happening. They officially confirmed that I was refusing to eat food, and the screws asked me three times.

I'd heard different stories in the past about Hunger Strikes, such as the pangs of hunger go within a few days, different things like that It wasn't my experience since for certainly 35-40 days I could still feel hunger and I was tempted to eat food. When I lost my appetite for food it was much later and it was the result of the effects of sickness and the effects of lack of food rather than and diminution of appetite.

There certainly was no noticeable physiological effects for the first twenty days. I felt a wee bit tired but I could sleep, read and write. To an extent this was tempered by the fact that we were thinking frantically about political developments and thinking about strategy. We were working as best as we could from within the confines of the prison to see if we could advance and develop the protest. We were listening form information; it wasn't a question of just being in a total vacuum, total isolation, just sitting staring. We were constantly receiving bits of information and we were constantly trying to send out wee suggestions. I suppose this activity would tend to use up some of our thoughts rather than sitting and dwelling on the lack of food.

After ten days in our original cell we were moved together from our blanket cells to a clean wing in H3; that was the first time that we were together. Brendan Hughes was OC of the Hunger Strike and he had handed the overall OC position in the jail over to Bobby Sands, at the beginning of the Hunger Strike. Brendan ordered us to stop the dirty protest when we began the Hunger Strike. We washed, had beds and wore prison pyjamas; there was no other clothing apart from the pyjamas.

In this period the screws routinely came four times a day and left our food in. The breakfast would be left with us until lunch, and lunch would be left until tea, the tea would be left until supper and the supper would be left until breakfast, and so on. The screws would record that nothing had been touched or eaten. I have since learnt that the prison authorities would measure the food with almost scientific accuracy to see if we had eaten or even touched the food. We were told by the prison authorities that there was no breach of the Hunger Strike recorded - it was certainly true in my case.

*Tomorrow, more of this bit of the interview. Buy the book to read the whole text.

Sunday, March 07, 2004

An Phoblacht / Republican News

May 18th, 1981

IRA Attempt to Kill Queen

Following the IRA bomb attack at an oil terminal on the Shetland Islands off the northern coast of Scotalnd whilst the British monarch, Queen Elizabrit, was on an official visit there last Saturday, the IRA pointed out that had they managed to place the bomb close enough to her then she would now be dead.

This dire threat was issued through the Irish Republican Publicity Bureau in Dublin and was signed by P. O'Neill. The IRA pointed out that:

"While the British occupation of Ireland continues then members of the British ruling class and administration will continue to be subject to IRA attacks. They have a choice. The Irish People, who live under British terror do not."

Explosion

The mid-day explosion at the Sullom Voe oil terminal Saturday was in the terminal's main power station, a quarter of a mile away from where the English Queen wand Prince Phillip were attending the terminal's inauguration ceremony. The pair were within minutes of formally opening the terminal, having arrived at the Shetland Islands in the royal yacht.

The explosion, caused by 7 lbs. of gelignite, was in Europe's largest oil terminal, owned by British Petroleum, where millions of gallons of oil are daily piped in from the North Sea oilfields. The explosion happened at a point high in the power station and debris was scattered over a congested area.

Saturday's IRA operation was a breach of Elizabrit's security comparable to a previous one, in 1977, during the Queen's jubilee year visit to the occupied six counties of Ireland, when bombs buried in the grounds of Coleraine University exploded shortly before, and after, the royal visit.

At that time, the British administration denied that bombs had been placed, but the IRA's claim was later confirmed by British army Brigadier James Glover, in captured "document 37", who admitted that a bomb on a long delay electronic timer had been inside the university grounds during the Queen's visit.

Breach

Last weekend, in order to minimise the loss of face to the British establishment caused by yet another IRA breach of their bejewelled mascot's security, the Scottish police, oil terminal officials, and the British media presumably orchestrated by British Home Office officials - played down both the attack and the IRA's Saturday lunchtime claims of responsibility to Reuters press agency and, via the Belfast republican press centre, to the media at large.

A reporter, who was covering the inauguration, said that when newsmen made on the sport enquires on Saturday lunchtime about the IRA's claim, they were told by the police that it was a hoax. Elizabrit's entourage, including security officers, dismissed it as a hoax and smiling senior police officers did nothing to disturb that view.

From Saturday to Wednesday the official line changed gradually, day by day. From no explosion on Saturday,; to an explosion by an unknown cause on Sunday evening; to an explosion, not due to a technical or equipment fault, as BP attempted on Tuesday to shift the blame away from themselves; and finally as Scottish police confirmed on Wednesday, to an explosion caused by high explosives!

May 18th, 1981

Following the IRA bomb attack at an oil terminal on the Shetland Islands off the northern coast of Scotalnd whilst the British monarch, Queen Elizabrit, was on an official visit there last Saturday, the IRA pointed out that had they managed to place the bomb close enough to her then she would now be dead.

This dire threat was issued through the Irish Republican Publicity Bureau in Dublin and was signed by P. O'Neill. The IRA pointed out that:

"While the British occupation of Ireland continues then members of the British ruling class and administration will continue to be subject to IRA attacks. They have a choice. The Irish People, who live under British terror do not."

The mid-day explosion at the Sullom Voe oil terminal Saturday was in the terminal's main power station, a quarter of a mile away from where the English Queen wand Prince Phillip were attending the terminal's inauguration ceremony. The pair were within minutes of formally opening the terminal, having arrived at the Shetland Islands in the royal yacht.

The explosion, caused by 7 lbs. of gelignite, was in Europe's largest oil terminal, owned by British Petroleum, where millions of gallons of oil are daily piped in from the North Sea oilfields. The explosion happened at a point high in the power station and debris was scattered over a congested area.

Saturday's IRA operation was a breach of Elizabrit's security comparable to a previous one, in 1977, during the Queen's jubilee year visit to the occupied six counties of Ireland, when bombs buried in the grounds of Coleraine University exploded shortly before, and after, the royal visit.

At that time, the British administration denied that bombs had been placed, but the IRA's claim was later confirmed by British army Brigadier James Glover, in captured "document 37", who admitted that a bomb on a long delay electronic timer had been inside the university grounds during the Queen's visit.